Post-Mortems#

A post-mortem is a document written after an incident that describes the incident, its impact, the root causes, and most importantly, what actions will be taken to prevent the incident from happening again. They are common in high-stakes engineering disciplines such as aviation. Unsurprisingly, they are also common in software engineering.

A post-mortem is not required for every incident. Partly, this is because post-mortems have opportunity cost. They take time and effort from other work. Partly, this is because adding operational reliability often incurs a penalty in other areas. For example, if a datacenter fails due to a physical issue[1], adding redundancy to prevent future issues means buying more equipment. Post-mortems are reserved for high impact, intolerable failures.

Post-mortems generally have 5 parts: Description, Impact, Root Cause Analysis, Lessons Learned, and Action Items.

See also

Further reading: Example Postmortem and Postmortem of database outage of January 31

Description#

The description contains a few paragraphs that describes the incident and incident response. Do not assume background information as the audience for a post-mortem might include the whole company in the present and in the future. The description should be written in the past tense.

Timelines are helpful to display events and actions in chronological order. Timestamps should be in the relevant local time and UTC.

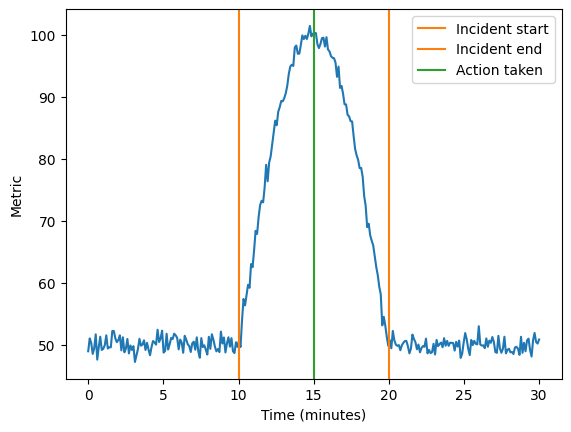

A graph with labeled vertical lines are helpful. Graphs allow readers to see the effects of events and actions on metrics. Many observability systems allow labeled vertical lines to be added to graphs. Below is a generated example.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

np.random.seed(123)

x = np.linspace(0, 30, 300)

before = np.random.normal(0, 1, 100)

incident = np.random.normal(0, 1, 100) + 50 * np.sin(np.linspace(0, np.pi, 100))

after = np.random.normal(0, 1, 100)

plt.plot(x, np.concatenate([before, incident, after]) + 50)

plt.axvline(10, label='Incident start', color='C1')

plt.axvline(20, label='Incident end', color='C1')

plt.axvline(15, label='Action taken', color='C2')

plt.xlabel('Time (minutes)')

plt.ylabel('Metric')

plt.legend()

<matplotlib.legend.Legend at 0x7fb740813510>

Blameless#

The purpose of a post-mortem is improvement, not to assign blame. Writing a post-mortem is not punishment, but rather a learning opportunity. Blamelessness is not just the nice or ethical thing to do. A culture of blame leads to a vicious cycle whose end result is more incidents. Blaming people also means not blaming the systems and processes around people that are also at fault.

To make post-mortems blameless, the humans involved in an incident or the response should not be named. Instead, replace names with the placeholder of title and number. For example, use engineer \(1, 2, \dots, n\) in place of engineer’s names.

Never make disparaging comments–written or verbal–about the way another engineer handled an incident. Hindsight bias can make their mistakes appear obvious than when the incident was ongoing.

Impact#

The impact section describes the effect of the outage. There are many types of impact an incident can have?

Technical impact. How many requests were dropped? How much did latency increase? How much data was lost? How long was the outage?

User impact. How many users were affected? Users could be external customers or others in the company.

Revenue impact. How much money was lost? Usually, this is the opportunity cost–the gap between revenue during the incident and normal revenue.

Geographical reach. How many regions were affected?

Root Cause Analysis#

Root cause analysis (RCA) is the process of identifying the root cause of a problem. RCA is essential to a post-mortem as, without knowing the root causes, determining the right corrective and preventative actions is impossible. You end up addressing symptoms and not diseases.

When performing RCA, try to look beyond human error[2]. Seeing past human error helps keep post-mortems blameless, but it is also easy to focus on the actions of people and ignore surrounding factors. For example, if a car hits a pedestrian, it is easy to say the root cause is driver error. But there often are other factors.

The road was wide, forcing the pedestrian to be exposed for a long time.

The incident took place at night. The street lights are dim.

The vehicle was big. The pedestrian was in the blind spot. The large vehicle didn’t decelerate enough to avoid a collision.

These environmental factors affect the likelihood that a human error snowballs into an incident.

5 Why’s#

5 Why’s is a technique invented by Toyota to understand why new product features were needed. Since then, it has been adapted for RCA. Starting from a problem, the technique repeats the question “Why?” 5 times to determine the root cause, which is the answer to the fifth why. The 5 number is arbitrary and should not prevent further questioning if the answer to the fifth why is not fulfilling.

A good example of 5 Why’s is a somewhat apocryphal story about a monument in Washington D.C.

Problem: One of the monuments in Washington D.C. is deteriorating.

Why is the monument deteriorating? Because harsh chemicals are frequently used to clean the monument.

Why are harsh chemicals needed? To clean off the large number of bird droppings on the monument.

Why are there a large number of bird droppings on the monument? Because the large population of spiders in and around the monument are a food source to the local birds

Why is there a large population of spiders in and around the monument? Because vast swarms of insects, on which the spiders feed, are drawn to the monument at dusk.

Why are swarms of insects drawn to the monument at dusk? Because the lighting of the monument in the evening attracts the local insects.

Conducting the 5 Why’s exercise suggests that the solution is to turn off the monuments lighting at dusk. This is a better solution than addressing the symptom of deterioration by scheduling more restoration work. Turning off the lights is cheaper and easier than frequent, expensive restorations which may prevent visitors from accessing the monument.

5 Why’s has some weaknesses. Namely, it encourages looking for a single root cause. Incidents often have multiple causes. In fact, if the affected system has redundancies, then any incident can only occur by failing at multiple points.

Fishbone Diagram#

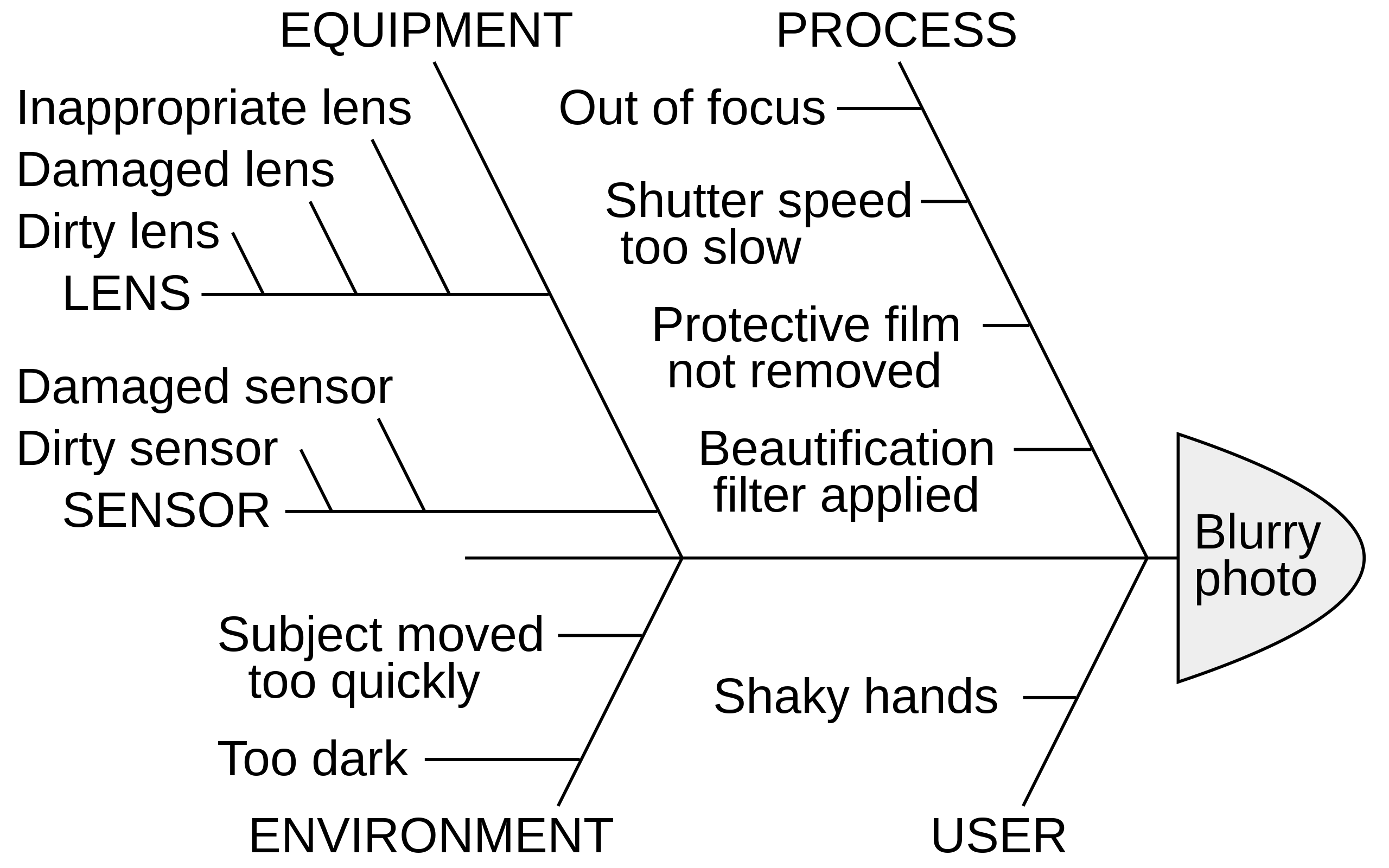

This tendency to look for a single root cause can be mitigated by branching why’s. The fishbone diagram formalizes this process. A Fishbone diagram has the problem on the right and the causes extended to the left. A backbone extends from the problem to the left. Pointing to the backbone are ribs which lists causes from a dedicated domain. Causes are listed along lines that connect to the ribs.

Fishbone diagrams are also called Ishikawa diagrams after their inventor, Kaoru Ishikawa. Below is an example of a fishbone diagram for a blurry photo.

Fig. 3 Fishbone diagram for a blurry photo. Image source.#

Lessons Learned#

Lessons learned summarizes all the learnings from the incident, impact analysis, and RCA. Lessons learned should explore what went well and what didn’t work. Did luck play a role in the incident? List lessons learned in a numbered list so they can referenced from other parts of the post-mortem.

Action Items#

Actions Items lists the actions the team following the incident. They should be tracked as tasks. Actions from post-mortem also merit separate tracking to ensure their completion in the face of competing priorities. Each action item has a priority, type, and owner. There are 2 critical types of actions.

- Corrective actions

Actions which correct or mitigate an incident. Ideally, the post-mortem is written after an incident is mitigated[3], so there will be few corrective actions.

- Preventative actions

Actions which prevent the incident from recurring in the future.

Actions should be derived from lessons. If a lesson is that a component didn’t work, it needs to be repaired or replaced. If a lesson is that a redundancy did work, it may need no action or to be strengthened. One practice is to have actions reference the particular lesson learned.

Reviews#

Once the post-mortem is written, it needs to be reviewed. Review the post-mortem with the team and any stakeholders. Review the post-mortem with an engineers outside the team. Cross-team review brings in fresh perspectives. Reviewing with outside engineers makes it hard to blow off writing a good post-mortem. A post-mortem is finished once all comments from reviews are addressed.

Once the review is complete, socialize the review. At a minimum, the post-mortem should go into a searchable repository with other post-mortems. The post-mortem can be shared via email, Slack, and the like with the wider organization.